The Diamond Model is a foundational cyber threat intelligence tool that you must learn how to use. It is a framework for analyzing cyber intrusions and mapping the relationships between the attacker, their tools, and the infrastructure used to perform an attack. Used effectively, it will reveal questions to ask about an attack, allow you to group intrusions, and track attack campaigns and threat actors.

This comprehensive guide will teach you the model, its seven axioms, and how to use it effectively through a practical demonstration. It also discusses when you should use the model and some of the limitations you may encounter in the real world.

Let’s start discovering the Diamond Model’s power and elevating our cyber threat intelligence skillset!

What is the Diamond Model?

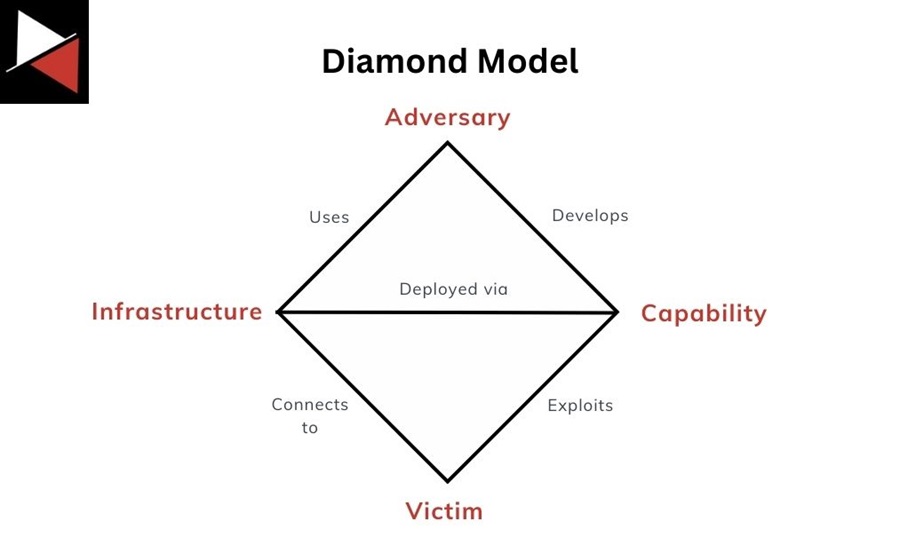

The Diamond Model is a simple framework for analyzing and understanding cyber threats. Defenders use it to organize and structure their intrusion analysis by categorizing data into one of its four components.

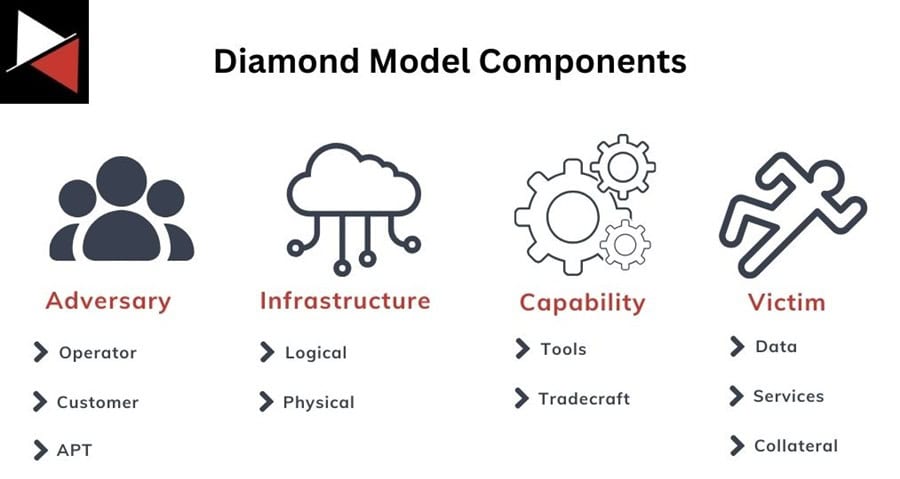

- Adversary: Who did the attack?

- Capability: How did they do it?

- Victim: Who was targeted?

- Infrastructure: What was used?

These four components are present in every cyber attack and relate to one another. In its simplest form, the model describes an “adversary deploys a capability over some infrastructure against a victim” (whitepaper), allowing an analyst to visualize the relationships between the key data points that fall under these categories.

Models like the Attack Kill Chain and MITRE ATT&CK matrix highlight the TTPs seen during an incident or the infrastructure used. However, they fall short of connecting the dots and generating tactical or strategic intelligence. The Diamond Model’s holistic view of cyber threats allows an analyst to better understand an intrusion, attack campaign, or adversary by taking a bird’s eye view of an intrusion, only showing key indicators.

Let’s examine each Diamond Model’s four components to better understand how it does this.

The Four Components of the Diamond Model

The four components that make up the Diamond Model are Adversary, Capability, Infrastructure, and Victim.

Each of these components is linked. For example, an Adversary develops a Capability and then uses Infrastructure to connect a Victim to deliver this Capability. Mapping intrusion data to each component reveals links between them. You can then better understand an intrusion by asking questions about the components involved and pivoting between them to find answers.

Here is an overview of each component.

Adversary

This is who is behind an attack. The nation-state, script kiddie, or cybercriminal who performed the attack. You can break the Adversary down into two roles:

- Adversary operator: The individual directly performing the attack.

- Adversary customer: The entity that benefits from the attack being performed.

An adversary can assume both of these roles or just one. Typically, high-profile cyber attacks involve multiple operation teams: one for initial access, another for developing the malware, and a third for exfiltrating data. The ransomware scene has adopted this structure, where you will have an initial access broker providing a service, a ransomware gang licensing their software, and an affiliate actually performing the attack.

The number of operations teams and the structure of who is actually performing the attack can get complicated quickly. Nation-states will use proxy groups, ransomware gangs will use affiliates, and the line between government operation and government-sanctioned operation can become blurry. As such, it is usually more productive to track the Adversary customer, who benefits most from an attack, rather than the specific individual or malware used.

This is not always the easiest thing to do using intrusion data.

To get started, track the online presence used, accounts seen (email, social media, etc.), and the intent of an attack rather than immediately labeling a state or gang. This will allow you to correlate these Adversary data points with other campaigns and more accurately attribute the attacks to an entity or campaign based on available data.

Capability

Capability refers to the tactics, techniques, and procedures (TTPs) the Adversary uses to perform the attack. This can be categorized into:

- Tools: The hacking tools, malware, or exploit used during an attack.

- Tradecraft: The hacking techniques used by the Adversary, such as exploiting living-of-the-land binaries and scripts (LOLBAS) or commands run on systems. The MITRE ATT&CK matrix covers these well.

When mapping Capabilities to the Diamond Model, you want to focus on specifics. General tools or tradecraft are not very useful if you want to track them. Focus on data points that stand out, usually represented by choices an Adversary will make, including specific malware configuration options chosen, custom malware used, and novel attack techniques or command-line options.

These can be considered key indicators. Indicators that remain consistent across intrusions, uniquely distinguish an attack campaign, and align with a phase of the Cyber Kill Chain. They are indicators you can use to track attack campaigns or threat actors, differentiate intrusions, and hunt for in your environment.

Infrastructure

An Adversary will deploy their Capabilities using Infrastructure. This is anything an attacker can use to deliver their capabilities. It can be physical, like a command-and-control (C2) server, or logical, like an email address or service account.

The attacker may use this infrastructure directly, such as a C2 server they connect to when performing their attacks, or something the Victim connects to, like a third-party file-sharing service where data is exfiltrated (e.g., file.io or Pastebin).

Almost anything can be infrastructure, from the process that runs a malicious DLL to the name badge an attacker cloned to gain access to the target building. Don’t just think of domains and IP addresses as infrastructure.

Here are some common types of infrastructure you will regularly come across:

- Service accounts

- Email addresses

- IP addresses

- Domains

- C2 servers

- Personas (social media handles, phone numbers, Telegram channels, etc.)

- Cloud services

- File sharing websites

- Tor nodes

- Compromised websites

Victim

The Victim is the recipient of the attack or “Capabilities deployed across Infrastructure by the Adversary.” The victim is either an individual or an organization with assets impacted by the attack (computer systems, networks, data, etc.). Victims rarely have a direct relation to the attacker; instead, they are connected by Infrastructure or Capability.

A Victim is just a means to an end for the Adversary. A threat actor’s intention is to compromise the confidentiality, integrity, or availability of the data or services a Victim controls. They do not care about the victim; they only care about the assets that the victim holds and the benefits they can gain from exploiting them.

It is also important to keep track of who the actual victim of an attack is. An attacker may compromise a software vendor to perform a supply chain attack against their real target. The actual victim of the attack will mean different things for your analysis.

An analyst can use the Diamond Model from different viewpoints:

- They could take the Victim’s view and look for Instrasture or Capability that links an Attacker.

- They could be an Infrastructure provider and look for Attackers targeting Victims using their services.

- They could even take the Attacker’s viewpoint and use Capability and Infrastructure to find a Victim.

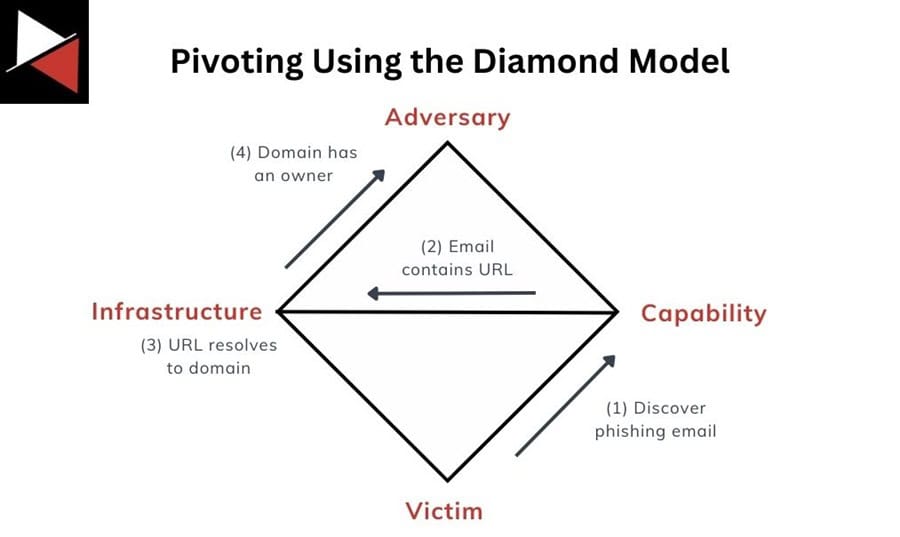

This pivoting aspect of the model, where you start at one component and move to another, is what makes it so useful for threat intelligence analysts. As an analyst, you can use the model to find questions that will generate leads, insights, and actionable intelligence for you to use.

To understand how these four components interact and to use the model effectively, you need to know the axioms on which the Diamond Model was built. These accepted assumptions are fundamental to using the model appropriately.

Diamond Model Axioms

Sergio Catalgrirone, the model’s co-creator, outlined the axioms that underpin the Diamond Model’s creation and operation in a blog post entitled The Laws of Cyber Threat: Diamond Model Axioms. These assumptions dictate how every cyber attack can be analyzed through the Diamond Model lens.

Axiom 1

“For every intrusion event, there exists an adversary taking a step towards an intended goal by using a capability over infrastructure against a victim to produce a result.”

This is the entire underpinning of the model. Every cyber attack involves an Adversary with an objective. This objective is achieved by developing a Capability (TTP) that is delivered to a Victim through some form of Infrastructure. Using this fundamental truth, you can analyze an attack and draw insights.

Axiom 2

“There exists a set of adversaries (insiders, outsiders, individuals, groups, and organizations) which seek to compromise computer systems or networks to further their intent and satisfy their needs.”

There are always bad guys somewhere who want to access your data or affect the services you provide, whether for financial, political, or personal gain. Understanding an adversary’s intention can help you develop strategies to defend against their attacks. This is why there is an Adversary in every attack.

Axiom 3

“Every system, and by extension every victim asset, has vulnerabilities and exposures.”

All computer systems and networks have vulnerabilities that a threat actor can exploit. You should assume that your systems will get breached at some point, regardless of how expensive or up-to-date they are. As such, you need to take precautionary actions that assume they will be breached and allow you to still protect your critical assets.

Axiom 4

“Every malicious activity contains two or more phases which must be successfully executed in succession to achieve the desired result.”

This relates to the idea of a Cyber Kill Chain proposed by Lockheed Martin, whereby an attacker must perform several steps to be successful in their cyber attack, from initial reconnaissance to actions on the objective. Assuming an attack must go through these steps gives you points where you can detect and prevent the attack.

Axiom 5

“Every intrusion event requires one or more external resources to be satisfied prior to success.”

This highlights that adversaries cannot exist in a vacuum. They require software, hardware, network access, and other technical or financial resources to perform an attack. This leads to the key components of Infrastructure and Victim. An Adversary must use Infrastructure and must have access to a Victim.

Axiom 6

“A relationship always exists between the Adversary and their Victim(s) even if distant, fleeting, or indirect.”

A threat actor will always target a Victim for a reason. The reason could be because they found out they were vulnerable to an easily exploitable vulnerability after running a mass scan across the Internet or that they were a specific political or financial target.

Axiom 7

“There exists a subset of the set of adversaries which have the motivation, resources, and capabilities to sustain malicious effects for a significant length of time against one or more victims while resisting mitigation efforts. Adversary-Victim relationships in this sub-set are called persistent adversary relationships.”

This relates to Advanced Persistent Threats (APTs). These threat actors have unlimited resources (time, money, and people) to sustain prolonged operations against a Victim. Who this is will depend on the adversary-victim relationship, and just because an adversary is persistent against one victim does not mean they are persistent against all victims.

A good example of APTs is nation-states like the United States, China, and Russia, which have been conducting long-term cyber operations against each other for decades.

The theory is great, but when should you actually use the Diamond Model? Let’s examine some use cases.

When to Use the Diamond Model

The Diamond Model has several main uses. Here are a few of the most common.

- Incident Response: When responding to a cyber incident, it is a great intrusion analysis tool to capture and analyze the relationships between an attacker, their TTPs, and the infrastructure they used to perform the attack. It allows analysts to visually map the technical details of how an attack happened and pivot between data points.

- Pivoting and Threat Hunting: The Diamond Model allows you to map out key components involved in an attack and ask questions about these components. Using the model to ask these questions can lead to new data points, intelligence insights, and generate hunting hypotheses.

- Threat Intelligence Analysis: The model is a great tool for organizing threat intelligence data related to an intrusion and grouping activity groups. This intelligence can then be analyzed to generate insights about an attacker’s motivations, tools, and tradecraft. Defenders can then proactively defend their organization from future attacks and make practical recommendations.

- Threat Modeling and Profiling: The Diamond Model maps the relationships between attackers and their motivations, capabilities, and tactics. This allows defenders to better understand their vulnerabilities and what assets will likely be attacked. Defenders can then create an accurate threat model to guide their defensive strategies and prioritize resource allocation.

- Security Awareness Training: Complete Diamond Models can be used as a learning tool when providing employees with security awareness training. They show the nature of an attack through a simple visual aid that can be easily explained to non-technical stakeholders to raise awareness of cyber threats.

For more details on when and how to use the Diamond Model, check out this great presentation by co-creator Sergio Caltagirone.

Limitations of the Diamond Model

The Diamond Model is a great tool for analysis, but it is still only a tool alongside other structural analytical techniques like the Cyber Kill Chain and MITRE ATT&CK matrix. Knowing when to use it and where it can fall short is vital to performing good analysis. Here are some of the Diamond Model’s limitations.

- Reductionist: The Diamond Model can oversimplify an intrusion by grouping everything into four generic categories. This can lead to analysts missing the nuance of an attack and failing to capture actors, tactics, and objectives that do not fit nicely into the model, leading to flawed intelligence assessments.

- Static Representation: The Diamond Model is only designed to capture static events and fixed relationships between adversaries, infrastructure, capabilities, and victims. In the real world, cyber threats are dynamic. Adversaries adapt their tactics, find new infrastructure, and their objectives evolve over time. This limits the value of prior intelligence generated using the model.

- Limited Context: The model often fails to capture the broader geopolitical, economic, and social factors that influence cyber threats and intrusions. This lack of context makes it hard for an analyst to understand an adversary’s motivations, intentions, and strategic objectives. The Diamond Model has an extension that addresses some of these limitations, but this can often overcomplicate analysis.

- Overemphasis on Attribution: The model emphasizes identifying and attributing intrusions to a specific adversary. Given the rise of false flag operations or nation-state-sponsored attacks, attribution is notoriously challenging in the cyber realm, making the model difficult to complete.

- Heavy Focus on Technical Aspects: The Diamond Model primarily focuses on the technical aspects of an intrusion (Capability and Infrastructure). These details are important but are not the full scope of an intrusion. Aspects such as social engineering, insider threats, and supply chain risks play a role not fully captured by the model.

Despite these limitations, the Diamond Model is still the best framework in cyber threat intelligence for visualizing the relationships present in cyber attacks and generating tactical and strategic intelligence.

An important point to note here is that analysts often misinterpret the Diamond Model and its relationship with attribution. The model is not about attribution. Attribution is a hypothesis based on the evidence you have collected; either you can make it or you guess. The model is more focused on grouping “activity groups” (clustering data together so you can ask what other data you can pivot to based on what you have already found).

Demo: The Diamond Model in Action

So, how do you actually use the Diamond Model? Let’s walk through a case study to demonstrate how to apply it to a real-world cyber attack. This will highlight how to use the model and best practices to follow.

Case Study

As our case study, we will use an excellent article by the DFIR Report team entitled “A Truly Graceful Wipe Out.” This report details a multi-stage intrusion in which attackers delivered Truebot malware via an email disguised as a fake Adobe Acrobat document to gain initial access and then deployed the destructive MBR Killer wiper.

We will only briefly cover the intrusion and focus on applying the Diamond Model to certain attack stages. I highly recommend reading the full report and following the DFIR team for more details.

Applying the Diamond Model

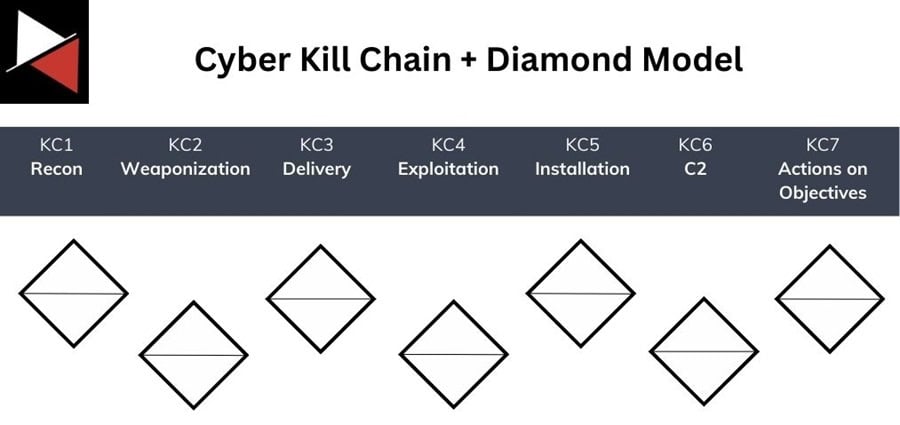

The best way to apply the Diamond Model to real-world use cases is to combine it with a complementary attack framework like the Cyber Kill Chain. This structured framework categorizes the different phases of a typical cyber attack and allows you to organize your analysis into a constructive attack narrative. It helps you add the technical details of an attack to your analysis.

Read Combining the Diamond Model, Kill Chain, and ATT&CK to learn more about how the diamond model, cyber kill chain, and MITRE ATT&CK complement one another.

Think of each stage of the Cyber Kill Chain as having an associated Diamond Model, where every data point or piece of evidence you collect related to that stage can be mapped to an Adversary, Victim, Infrastructure, or Capability.

Aim to fill each Diamond Model component with as much data as possible for every stage of the kill chain. Some stages will be more difficult than others, and you may find that some stages don’t involve an Adversary or Victim at all.

Nevertheless, one component must be populated in each stage of the kill chain, at least between stages two (Weaponization) and six (Command and Control), to declare your analysis of an intrusion complete.

Any gaps you find represent an intelligence requirement that must be fulfilled with supplementary data. This could include additional intelligence gathering, malware analysis, reverse engineering, or digital forensics. Based on your data, you can also assign each link between components a confidence level. This lets you qualify assessments made using the model with estimative language.

This example demo won’t map every stage of the kill chain (this is left as an exercise for the reader). Instead, it focuses on the Delivery, Installation, and Command and Control (C2) stages.

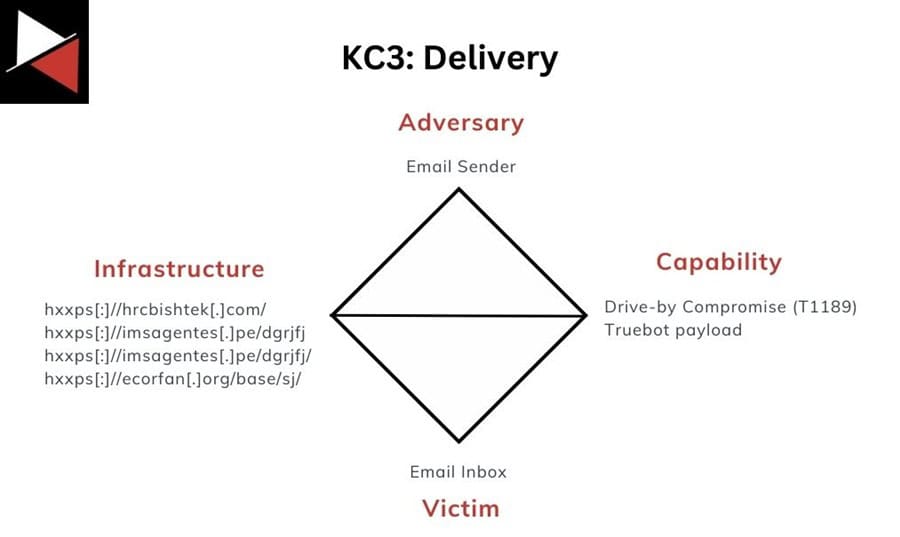

Delivery

The threat actor behind this intrusion used email as their initial delivery mechanism. They sent a phishing email to employees that redirected through a series of URLs before downloading a fake Adobe Acrobat document that was actually a Truebot malware executable.

The components related to this stage of the attack are as follows:

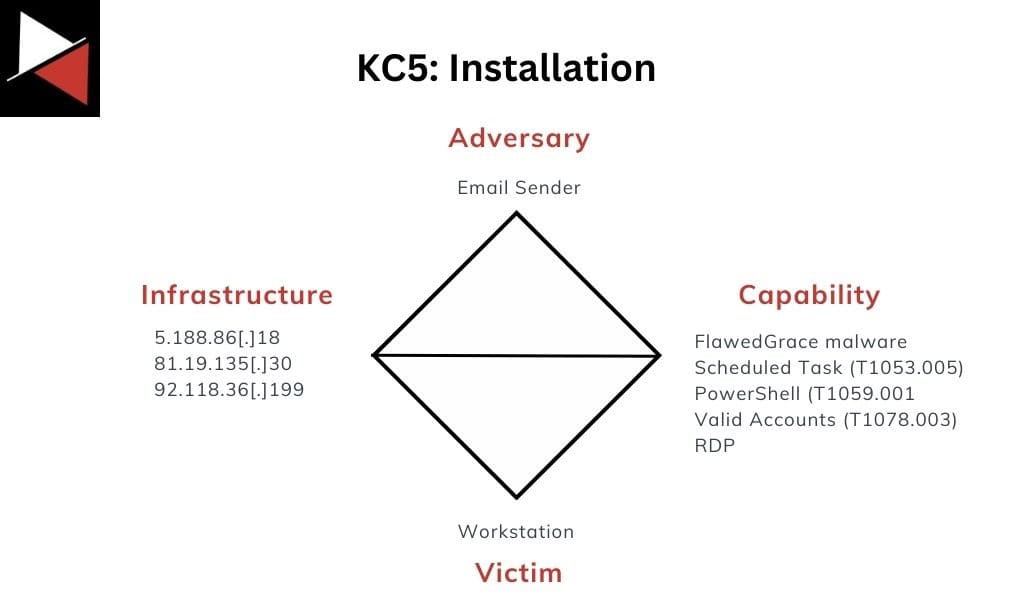

Installation

After gaining initial access to a corporate workstation, the attackers used scheduled tasks and local administrator accounts with RDP access for persistence. These persistence mechanisms, created using PowerShell, gave the attackers an RDP connection to the compromised workstations.

The components related to this stage of the attack are as follows:

The IP addresses are ones the FlawedGrace malware reached out to as part of the scheduled tasks created and RDP connections made.

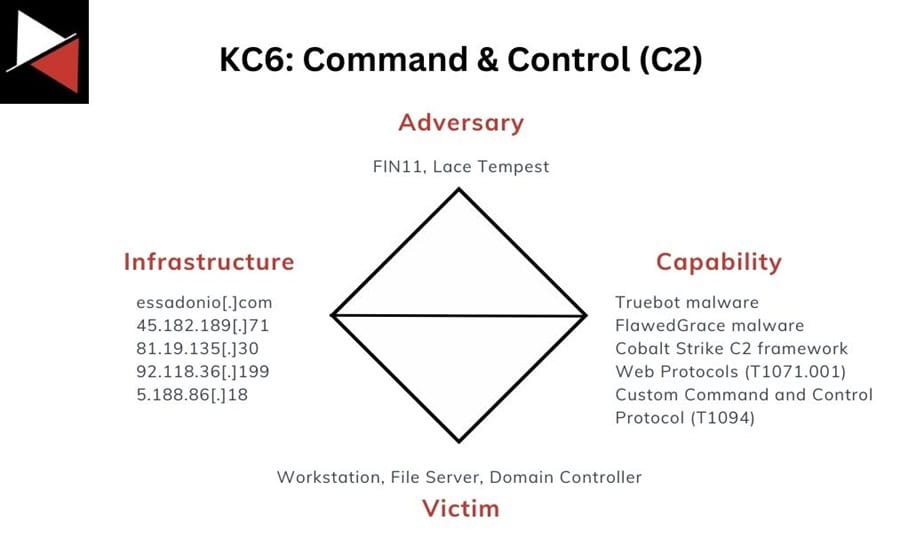

Command and Control

Finally, for command and control over the systems they compromised, the attackers deployed Truebot, FlawedGrace, and Cobalt Strike malware to pivot around the corporate network and perform malicious actions. They communicated with their C2 agents through common web protocols (HTTPS) and custom protocols on port 443.

The components related to this stage of the attack are as follows:

The network infrastructure used by the adversary was seen previously in campaigns by FIN11 and Lace Tempest, meaning they can now be labeled as the Adversary. The new IP addresses now relate to the C2 servers used in the attack.

Once you have concluded your analysis of each kill chain stage, you can merge your individual Diamond Models into one big one, as the team at the DFIR report has done. However, it is often useful to keep the stage-specific models to compare them against other intrusions and cluster data together to track capabilities, campaigns, and actors at each stage of an attack.

These three Diamond Models allow you to begin asking questions about your data set, pivot to new intelligence, and connect the dots:

- What Adversary is related to the Infrastructure I am seeing?

- What Capabilities do these Adversaries have that I could look for in my environment?

- What goals does the Adversary try to achieve, and what vulnerabilities will they exploit?

Conclusion

The Diamond Model is an essential tool in your cyber threat intelligence arsenal. It allows you to ask the right questions about your intrusion dataset and pivot to find the answers. All CTI analysts should know and understand how to use this model to perform intrusion analysis that can be shared with the wider cyber security community.

This article showed you how to use the Diamond Model to perform effective analysis and highlighted use cases where this model shines. It also discussed potential limitations of the model that you may encounter in the real world. To start using the model, use the practical demonstration showcased as a building block and map out the rest of the attack described in the DFIR Report article. Good luck!

The Diamond Model is just one structured analytical technique you should know how to use to become a CTI analyst. Follow the ongoing series Structured Analytical Techniques for more!

Frequently Asked Questions

What Are the Four Main Features of the Diamond Model?

The Diamond Model describes the relationships within a typical cyber attack. To do this, it uses four main components:

- Adversary: The perpetrator of the cyber attack. This could be an individual operator or the entity that benefits from the attack, including their intent, motivations, and objectives.

- Capability: The tools (hacking tools, malware, exploits) and tradecraft (TTPs) the attacker uses during an intrusion.

- Infrastructure: The vehicle the attacker uses to deliver their capabilities and perform the attack. It can include email addresses, online personas, phone numbers, C2 servers, compromised websites, domains, IP addresses, Tor nodes, service accounts, file-sharing websites, and cloud services.

- Victim: The intended target of the attack. This is not to be confused with targets used as collateral, such as software vendors, hosting services, or contractors.

What is the Diamond Model of Intrusion Analysis?

The Diamond Model is a conceptual framework used in cyber security to analyze and understand cyber threats, intrusions, or attacks. It uses four key components: adversary, victim, infrastructure, and capability. These components provide defenders with a structured approach for organizing and visualizing the relationship between an attacker, the victim, and how an attack happened.

It is used in incident response, cyber threat intelligence, threat modeling, threat profiling, and security awareness training to visually show the relationships between these four components and explain how an attack happened.

Who Created the Diamond Model?

Sergio Caltagirone, Andres Pendergast, and Christopher Betz developed the Diamond Model over several years within the intelligence community. It was then declassified and released publicly in a paper titled “The Diamond Model of Intrusion Analysis” by security researchers Andrew P. Moore, Benjamin Edwards, Jared Ettinger, and Richard Harang. This was presented at the International Conference on Cyber Conflict (CyCon) 2014.