Threat actors are everywhere:

- “APT41 launches DocuSign-themed phishing campaign…”

- “Scattered Spider raises the sophistication of its SIM swapping attacks…“

- “Sandworm attacks Ukraine power grid…”

But which ones are relevant to your organization? Who is going to try to target you? How do you start answering these questions?

To identify which threat actors to focus on, you must know a little bit about them. What motivates them? What is their intent? What capabilities does a certain group have? Answering these questions lets you determine which threats you must prioritize protecting against.

This guide walks you through the common types of threat actors and their attributes and how to use this knowledge to match your cyber security investments against those likely to attack you. Empowering you to tailor your defenses against those who are targeting you. The first piece of the puzzle is understanding who is doing the targeting. Let’s jump in!

Threats and Threat Actors

Before discussing threat actors, you must understand what “threats” are and how they relate to cyber security.

Cyber security is all about managing risk. It is ultimately the practice of mitigating (or reducing) the risks an organization faces while conducting business in cyberspace. This involves protecting an organization’s people, processes, and technology as it aims to fulfill its business objectives.

You use “security controls ” to manage risk. Cyber threat intelligence (CTI) advises leaders on which security controls to implement to manage a business’s risk best.

Risks are the probable damage a threat can cause when exploiting a vulnerability. This brings up two important definitions: threat and vulnerability:

- Threat: Anything that can be used to exploit a vulnerability and cause damage to an organization (e.g., a person, method, tool, or technique).

- Vulnerability: A weakness that a threat can exploit to break into the system or do something they shouldn’t be able to do.

A risk occurs when a vulnerability is exposed to a threat that has the capability to exploit that vulnerability. If this criterion is not met, then there is no risk. For instance, if a popular VPN software has a vulnerability. This is only a risk if a threat has the capability to exploit it and your organization uses that VPN software.

It is at the intersection where threat meets vulnerability where risk occurs.

To manage risks, you can perform two types of assessments:

- A risk assessment: This assesses an organization’s vulnerabilities in relation to the threat it faces. It is organization-specific and focuses on how the organization’s uniqueness would be of interest to a threat (e.g., what technology is used, what data the company holds, etc.).

- A threat assessment: This considers the overall capability and intent of the threat. It is threat-focused and separate from the organization, often including a threat actor’s tactics, techniques, procedures (TTPs), or kill chain.

These two assessments inform your risk management strategy. This strategy outlines how you prioritize threats and security controls to combat them to identify, assess, and manage your business’s risks.

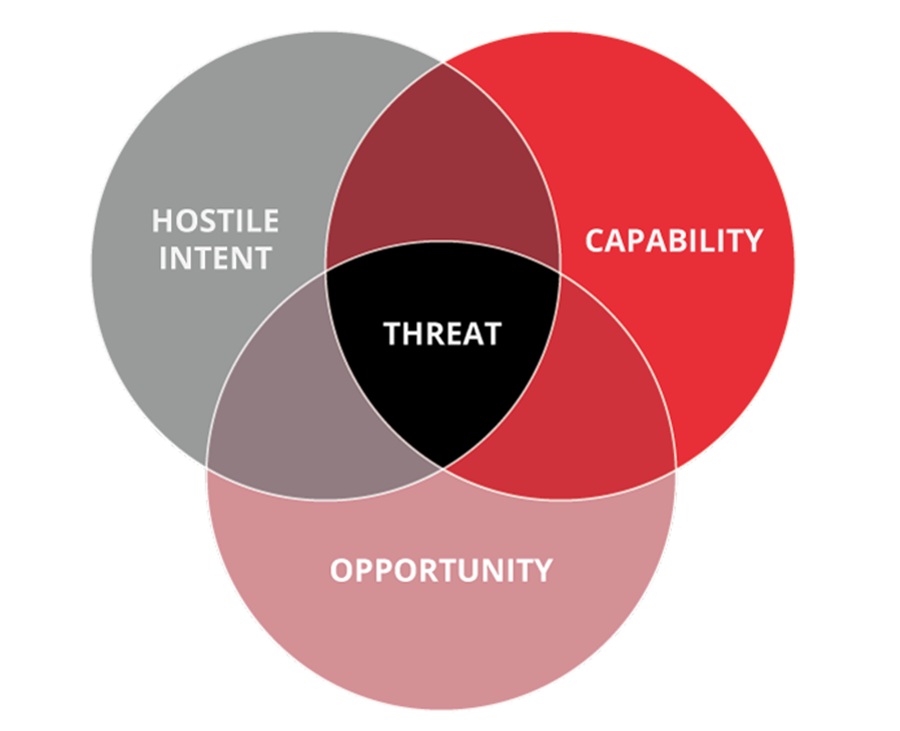

CTI allows you to take a threat-focused approach to managing risk by mapping specific threats to the risks they pose to your organization. Many cyber security folks break down threats into hostile intent, capability, and opportunity to do this effectively.

This allows you to better identify threats relevant to your organization by asking questions like:

- Why would a threat target my organization? (intent)

- What is the ability of a threat to achieve their hostile intent? (capability)

- Are their attack vectors a threat that could be exploited? (opportunity)

Answering these questions allows you to identify what threats your business faces. However, this abstraction is often difficult to apply practically to your business or when describing real-world threats to management. People understand vulnerabilities (they are in the news every day), but understanding threats is challenging when you can’t put a face on them.

Often a better way to describe a threat to a business is to use “threat actors” and create a narrative in which these are the bad guys you must fight. To simplify this, there are three main archetypes that a threat actor can fall under:

- Nation-state: Sponsored by a government or other organization and may have a political or ideological agenda. They may target organizations or individuals to steal sensitive information or disrupt critical infrastructure.

- Cybercriminal: Motivated by financial gain and often targets individuals or organizations to steal sensitive information, such as personal or financial data, or to extort money through ransomware or other malicious activities.

- Hacktivist: Motivated by political or ideological beliefs and may target organizations or individuals to disrupt operations or steal sensitive information as a form of protest.

Some people view insider threats as another potential threat actor. These individuals have legitimate access to an organization’s systems and resources but misuse their access to cause harm, either intentionally or inadvertently. The threat they pose is related to the threat actor they are linked with (e.g., an insider linked to a nation-state poses more of a threat than an insider linked to a hacktivist group). Hence, categorizing them as a threat vector is often more useful.

Each of these groups is made up of a set of attributes:

- Motivation: Why the actor does what they do.

- Intent: What an actor is hoping to achieve.

- Capability: An actor’s ability to achieve their intent.

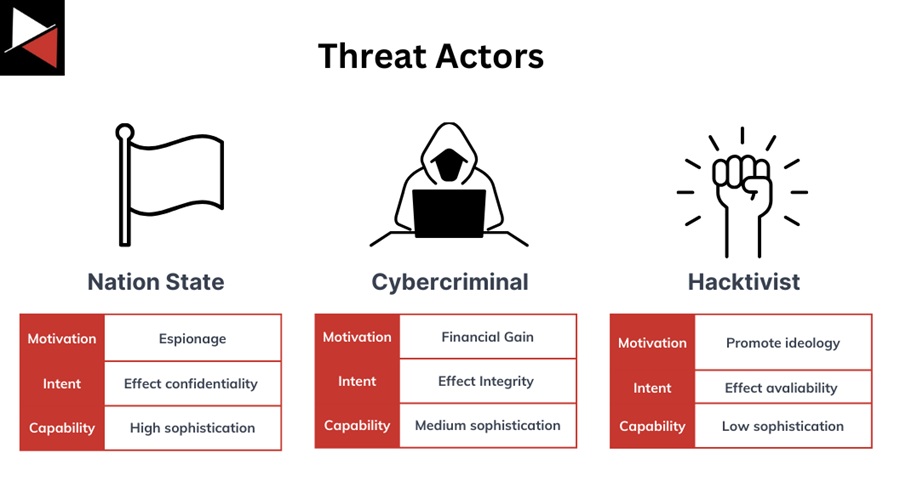

Here is a generic overview of how each attribute maps to each main threat group.

Nation-state

- Motivation: Intellectual property theft, espionage, destroying critical infrastructure.

- Intent: Effect the confidentiality of information (e.g., steal the information).

- Capability: High sophistication.

Cybercriminal

- Motivation: Financial gain.

- Intent: Effect the integrity of the information (e.g., ransomware attack)

- Capability: Medium sophistication.

Hacktivist

- Motivation: Promote ideology.

- Intent: Effect the availability of information (e.g., DDoS attack).

- Capability: Low sophistication.

These attributes (and main groupings) allow you to categorize threat actors and the threats they pose to your organization. They provide a framework for dividing the people who may target your organization into groups and assessing the credibility of the threat they pose.

This categorization allows you (as a CTI analyst) to help your intelligence consumer better understand the threat landscape by simplifying all the potential “threats” a business faces. It is like defining a piece on a chess board. You are giving it a label to define its power for the CTI consumer. The consumer can then plan their strategy accordingly based on that piece.

All models like this simplify reality and potentially exclude some important details of the true threat. For instance, some nation-states have the intent to steal money rather than perform espionage (e.g., North Korea). To account for potential outliers, describing the threat’s individual attributes (motivation, intent, capability) is important.

Outliers

Dividing threat actors into nation-states, cybercriminals, and hacktivists is often easy based on their motivations and capabilities. However, depending on the specific situation, these groups can interact and cross over in various ways, mudding the waters.

For example, a patriotic hacktivist may hack for a nation-state, or a cybercriminal may be supported by a nation-state because it helps with their mission.

Also, the line between these groups is not always clear-cut, and some actors may fit into multiple categories or change their tactics and methods over time. A nation-state actor may start conducting cyber espionage but later switch to destructive attacks, or a criminal organization may begin using ransomware to extort victims but later transition to stealing sensitive information.

This gives rise to outliers or “inbetweeners” who sit between the broad definitions of nation-state, cybercriminal, and hacktivist. Common inbetweeners include:

- State-aligned hacktivists: Hacktivists who hack for a state (e.g., Cyber Berkut, Syrian Electronic Army).

- State proxy: Cybercriminals who hack for a state (e.g., Russian ransomware gangs). However, there is a difference between cybercriminals and nation-states doing cybercrime (e.g., Lazarus Group hacking for money). Groups can also be state-backed, state-sanctioned, and state-tolerated relationships.

- Hybrid actors: Cybercriminals and hacktivists can also cross over where they do a criminal activity based on political/ideological motivation and tell people about it (e.g., The Dark Overload).

These in-between groups are often the most interesting to monitor because they tend to draw their strengths from different groups and be more unpredictable. This makes their motivation and targeting challenging to predict.

A great book that details these “outliers” is Tim Maurer’s “Cyber Mercenaries: The State, Hackers and Power.” The video below is a discussion of the book.

The rest of this article explores motivation, intent, and capability more closely so that you can more accurately define threat groups that may target you (and describe them to your intelligence consumer).

Motivation

The motivation of a threat actor answers why they are doing what they are doing. Why would a nation-state target your organization? Why would a cybercriminal try to phish your employees? Why would a hacktivist with an environmental ideology target your business operations?

What Motivates Nation-States?

Historically, nation-states have been motivated by intellectual property theft. This dates back to the early 2000s when China conducted a series of cyber operations against the United States. The modus operandi for these operations was to steal sensitive data to use back in China for technological advancement.

The low barrier of entry to perform these attacks and their relative cheapness compared to other nation-state operations (e.g., military intervention) have led to almost every nation-state developing cyber capability. Everybody is hacking everybody!

However, post-2010, the motivation for nation-states to perform cyber operations has shifted from purely espionage to destructive attacks on critical infrastructure (Ukraine, 2015) and for financial gain (Bangladesh Bank heist, 2016). That said, espionage has also remained a prominent motivation with disinformation campaigns (US presential election and Brexit, 2016) and supply chain attacks (SolarWinds, 2020 and XZ backdoor, 2024).

Even though nation-states are prominent threat actors in cyberspace, comparing them to the threat actors most businesses must contend with is an unfair comparison. Nation-states operate on an entirely different scale from cybercriminals and hacktivists. Cyber is just one tentacle of the state whose resources are infinite compared to most businesses. If they want to hack you, they will.

In this sense, defending against a nation-state is an aspirational goal; for most organizations, it is beyond their threat model. They are discussed here to show the spectrum of threat actors out there.

What Motivates Cybercriminals?

Cybercriminals are motivated by financial gain. How they achieve this (e.g., their intent) will vary. They may choose to deploy ransomware or target Industrial Control Systems (ICS) for digital extortion, steal sensitive corporate information and auction it off, or just scam you out of money.

Post-2018, cybercriminals have predominately focused their efforts on ransomware and built an entire ecosystem around it. They target businesses and critical infrastructure with the aim of heftier payouts. This has been driven by the rise of commodity and service-based malware, cryptocurrency, and the ubiquity of personal data that can be held for ransomware.

Also, on an individual level, cybercriminals are more motivated to perform cybercrime than other more traditional criminal ventures (e.g., selling drugs, running guns, etc.) because it is less risky to their personal health (less likely to die doing it).

What Motivates Hacktivists?

Hacktivists are motivated by their ideological beliefs. Hacktivism is a global phenomenon driven by social issues (usually left-leaning) and rises from the intersection of people and technology. These social issues range from environmentalism to anti-capitalism to anti-censorship, many of which are derived from libertarian goals (personal freedom, anti-establishment, etc.).

Winning for hacktivists is making their cause relevant in the public sphere, going from underground support to mainstream news coverage, public support by the masses, and inciting change.

There is also a low barrier to becoming a hacktivist (e.g., you can post stuff online or download a point-and-click tool to perform a DDoS attack). This makes it an attractive cause for young people who see it as less risky than other activist pursuits.

Hacktivists movements can be morally good or bad (e.g., Women’s rights vs. Nazism), but more importantly for you, they can be good or bad for the organization you work for. Most businesses are concerned with anti-capitalist social movements that target their business operations. Here, it is important to distinguish between people posting content that supports a hacktivist movement and those actively performing cyber operations.

For every person conducting hacktivist operations, hundreds or thousands are just posting stuff online. As such, a hacktivist group often appears more supported and resourced than it actually is.

An interesting facet of hacktivists compared to cybercriminals and nation-states is that they can die out. A strong hacktivist movement one day can quickly become insignificant within a year if the social movement dies out. Unfortunately, cybercriminals and nation-states do not decline this rapidly.

Measuring Motivation

Understanding these motivations allows you to determine who will target your organization more accurately. Depending on your organization, a specific threat actor may be more motivated to attack you than others.

For instance, if you are a large petrochemical business, a hacktivist group with a strong environmentalist ideology will be more motivated to target you and willing to dedicate more resources to achieve their objective.

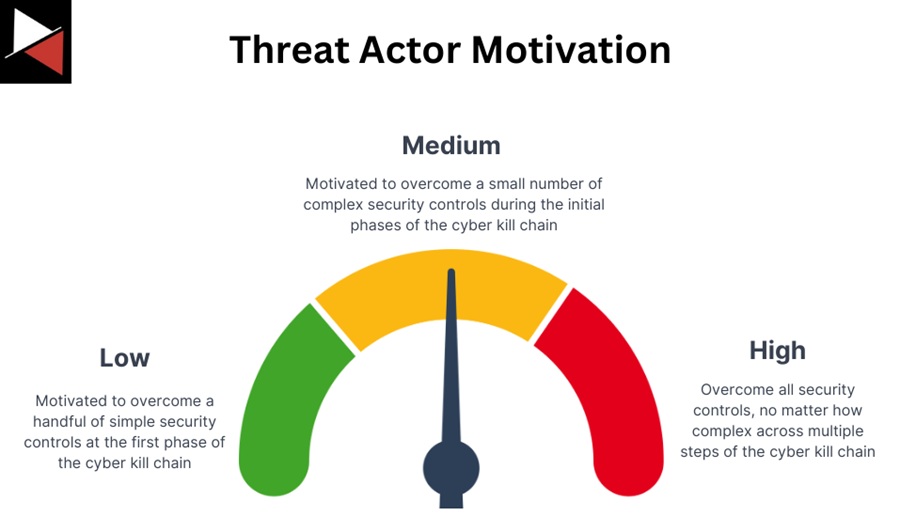

You can generally split motivation into low, medium, and high.

Low Motivation

Threat actors with low motivation may not have a specific goal and may be more interested in causing disruption or damage for their own sake. They may also be less organized, less well-funded, and have lower technical expertise than those with medium or high motivation.

Individuals or groups interested in causing chaos could be examples of low motivation. They are only motivated to overcome a handful of simple security controls at the first phase of the cyber kill chain. Low-skilled hacktivists and script kiddies usually have low motivation.

Medium Motivation

Threat actors with medium motivation may have a specific goal but are less willing to take significant risks to achieve it. They may also be less organized and well-funded than those with high motivation and have a lower level of technical expertise.

Examples of medium motivation could be hacktivists or a criminal group with a specific goal but fewer resources to achieve it. They are motivated to overcome a small number of complex security controls during the initial phases of the cyber kill chain.

High Motivation

Threat actors with high motivation are those who have a clear and strong goal and are willing to take significant risks to achieve it. These actors are typically highly organized, well-funded, and have high technical expertise.

Examples of a highly motivated group could be a nation-state performing espionage or a cybercriminal gang with a specific goal of stealing large amounts of money. They are extremely motivated to overcome all security controls, no matter how complex, across multiple steps of the cyber kill chain.

This is not to say that hacktivists can’t be highly motivated. Instead, they often recognize they cannot overcome complex security controls and target their attacks against less sophisticated organizations or focus on disruptive attacks at the earlier stages of the attack lifecycle.

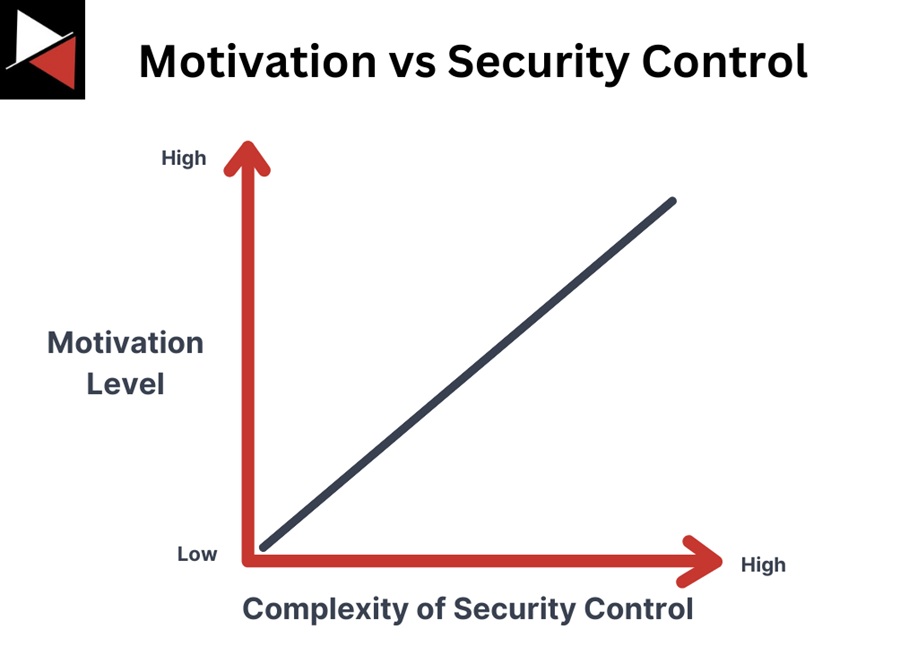

Typically, the more motivated a threat actor is, the more complex your security controls need to be to defend against them. To help visualize this, you can plot the motivation level on the Y axis and the complexity of your security controls on the X axis.

The categorizations listed can be useful for security teams to quickly assess a threat actor’s motivation and prioritize the most critical threats. Additionally, by understanding a threat actor’s motivation, teams can develop more effective countermeasures that protect the assets most likely to be targeted during an attack.

A threat actor will fulfill their motivation through their intent.

Intent

Intent is what the threat actor hopes to achieve. It can be thought of as the “effect” the actor wants to have on the target or what component of the CIA triad they want to impact.

It’s easier to quantify an actor’s effect on a thing rather than the intent they have in their mind because it’s very difficult to know a threat actor’s true intentions. You never get access to their mission briefing (or the ability to read their mind).

Here are some examples of intent:

- “Hacktivists want to affect the availability of company XYZ’s data by performing a DDoS attack.”

- “Ransomware gang ABC wants to affect the integrity of company XYZ’s data by holding it for ransom.”

- “Nation-state APT123 wants to affect the confidentiality of company XYZ’s propriety information to use for their nation’s technological advancement.”

These examples are broken into “actor” + “intent (effect)” + “target asset.” This format makes it easier for an intelligence consumer to see the threat picture. The language allows them to prioritize those threats based on their business objectives.

For instance, “I am more concerned about our sensitive database (confidentiality) than our website going offline (availability).”

Understanding a threat actor’s intent is important because it helps organizations better understand the nature of a threat and take more effective measures to protect against it. This includes technical defense, organizational procedures, threat hunting, incident management, and communication.

You must also factor in the threat actor’s capability to prioritize these measures.

Capability

Capability is the threat actor’s ability to achieve their intent. Your ability to understand how an attack happened and the capability of a threat actor makes or breaks you as a CTI analyst. You must be able to accurately assess an actor’s capability to determine if they should be prioritized as a threat.

For example, a hacktivist group might want to attack a nuclear power plant and bring down its critical infrastructure. However, the capability required to do this is very advanced. It would require resources only a nation-state would have access to.

Unfortunately, measuring capability can be challenging.

- Do you measure it by the sophistication of the malware used by a group?

- Is it the access a group has to zero days?

- Can you base capability on how obfuscated the malware used during an attack is?

All these measures of capability focus on malware (often because it’s the easiest threat vector to measure). However, malware does not provide the full picture. Malware is just one weapon that a threat actor can use. Using it exclusively to define the threat’s capability confuses a cyber attack and the malware used.

You must distinguish between the threat actor performing an attack and the malware used.

Threat actors often use commodity malware during an attack to save on resources (if you don’t need custom malware, then why write it?). Many security teams will see this malware as tangible and easily accessible evidence, using it as a collection source. They can then fall into the trap of misusing this malware and tracking the malware author rather than the threat actor using it.

The configuration of the malware used is a better tracking point. This is often more unique to a threat actor and can correlate with multiple intrusions, helping you track campaigns, enrich threat hunts, improve incident response, and write better detection rules.

So how do you measure capability?

There are two approaches you can take to holistically measure a threat actor’s capability:

- You can base capability on the probable force that a threat actor can apply to an asset or against a security control (FAIR Institute). For example, a nation-state can apply considerably more force to bypass a security control than a hacktivist group. This is great in theory but often too abstract to be useful.

- To ground capability to reality, you can measure it using evidence that a threat actor can perform a certain type of attack.

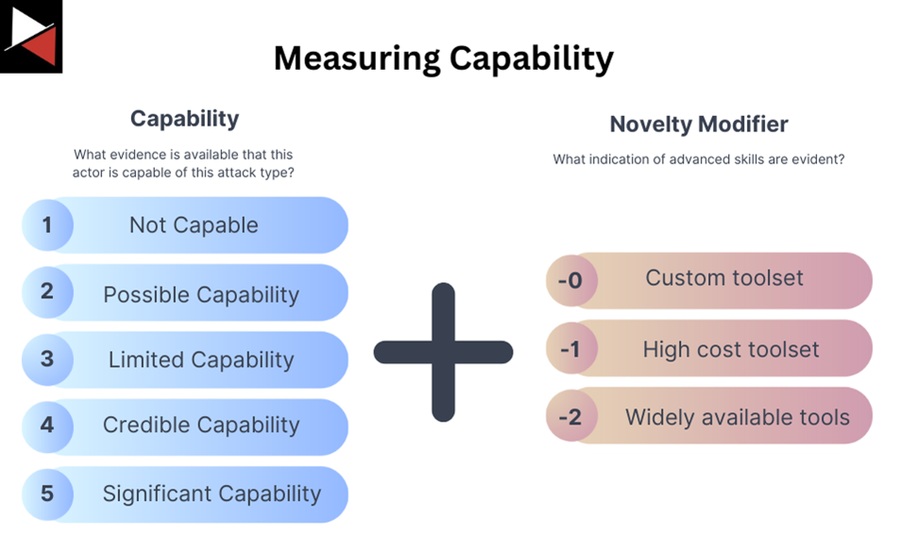

In an excellent blog post, Andy Piazza (SANS) ranks capability on a scale of 1-5 based on the evidence of the threat actor performing that attack in the past. He also added a novelty modifier to “give some credit to the Blue Teamers’” ability to defend against common TTPs and the threat actors’ “ability to write custom toolsets and move quietly in an environment.”

Capability: What evidence is available that this actor is capable of this attack type?

| 1 | Not Capable | No evidence of operational capability; feasibility unconfirmed. |

| 2 | Possible Capability | Some evidence of operational capability is limited, and sources are limited. |

| 3 | Limited Capability | Some evidence of operational capability; limited sources. |

| 4 | Credible Capability | Credible evidence of operational capability; moderately confirmed. |

| 5 | Significant Capability | There is significant evidence that the threat actor previously conducted this type of activity; multiple trusted sources confirmed. |

Novelty Modifier: What indication of advanced skills are evident?

| -0 | Custom toolset per campaign with demonstrated living off-the-land capability. |

| -1 | Limited availability/high-cost toolset used in multiple campaigns. |

| -2 | Toolset is generally available. |

You can then take these criteria, add them up, and map them to the following scale.

| Low Capability | Medium Capability | High Capability |

|---|---|---|

| 0-1 | 2-3 | 4-5 |

For instance, there is significant evidence that the Sandworm threat group is capable of hacking into ICS. They also use custom tools and living-off-the-land techniques to do this in each campaign (MITRE C0028). As such, Sandworm has a high capability.

So, what does this all mean? How does knowing threat actors and their attributes help you defend against them? Let’s make this all practical.

Bring It All Together

Knowing threat actors and their attributes helps you identify who is likely to target you, what assets they are likely to go after, and who you should prioritize defending against based on their capabilities.

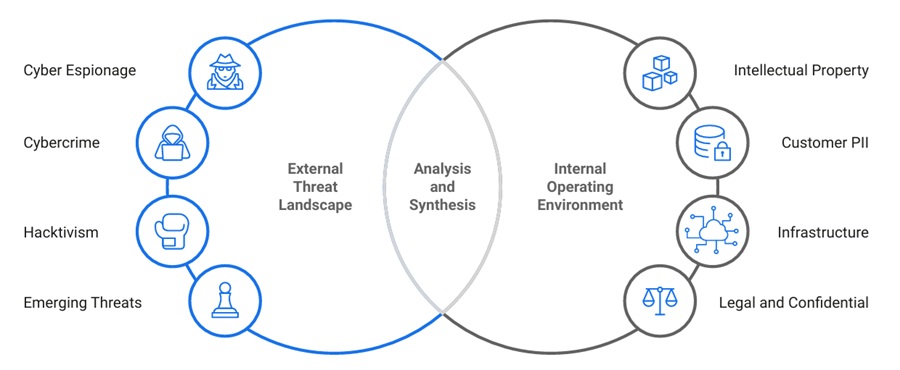

Identifying which threat actors are likely to target you and what assets they will target is part of creating a threat profile. This profile maps the external threat landscape (threat actors) to your IT estate.

Going one step further, creating a threat profile for your organization is part of the broader effort to define your organization’s threat model. Using numerous frameworks and techniques, you will systematically identify, evaluate, and prioritize the risks that threaten your systems, applications, or overall security.

Some of these include:

- Threat profiling threat actors and their TTPs

- Quantifying Threat Actors with Threat Box

- Crown Jewel Analysis (CJA)

- Threat and risk assessments

- Intelligence Preparation of the Cyber Environment (IPCE)

Understanding who will attack you is integral to building a robust threat model tailored to your organization. Once you have your threat model, you can then start developing your intelligence requirements and move your CTI program forward.

Frequently Asked Questions

What Is an Example of a Threat Actor?

A threat actor is an individual or group that poses a threat to an organization by compromising the confidentiality, integrity, or availability of its systems, networks, or data. Common types of threat actors include:

- Nation-States: Government-backed groups that engage in cyber espionage and cyber warfare (e.g., Cozy Bear, APT41, etc.).

- Cybercriminals: Groups that engage in cyber operations for financial gain (e.g., fraud, ransomware attacks, and stealing data for profit).

- Hacktivists: Groups motivated to perform cyber attacks to further political or ideological social movements (e.g., Anonymous)

What Is the Difference Between a Hacker and a Threat Actor?

The difference between a hacker and threat actors comes down to authorization and context. A hacker is anyone who aims to manipulate or bypass systems. They may have authorization to do this as part of a security testing exercise or perform this activity without authorization (illegally) for personal gain.

A threat actor is a broader term that includes any individual or group that poses a threat to an organization’s cyber security. This includes nation-states, cybercriminals, and hacktivists. Cybercriminal and hacktivist groups encompass what most people think of in terms of “hackers.”

What Is a Threat Actor and Threat Vector?

A threat actor is an individual or group that poses a threat to an organization. They are the ones behind the attack. A threat vector is a method or pathway a threat actor uses to exploit a system. It’s the entry point for an attack and describes how it happens. For example, a cybercriminal (threat actor) sends a phishing email (threat vector) to steal banking credentials.

What do you mean by Threat Actor?

A threat actor is an individual or group that poses a threat to an organization by compromising the confidentiality, integrity, or availability of its systems, networks, or data. They are the entities performing the cyber attack. The primary motivations for a threat actor include financial gain (cybercriminal), espionage (nation-state), and political activism (hacktivist).