The Analysis of Competing Hypotheses is a structured analytical technique that empowers you to make robust decisions through logical reasoning and critical evaluation. It thoroughly compares and contrasts multiple hypotheses to generate a complete explanation informed by the available evidence.

This is a must-learn technique if you want to become a cyber threat intelligence analyst or improve your intelligence analysis skills, and this guide will teach you everything you need to know.

You will learn the seven-step process, when to use this analytical technique, and the potential limitations you may encounter in the real world. Finally, you will see this analysis technique in action with a practical demonstration to solidify your learning.

Let’s begin by exploring the origins of the Analysis of Competing Hypotheses method to gain a full understanding.

What is the Analysis of Competing Hypotheses?

The Analysis of Competing Hypotheses (ACH) is a structured analytical technique that allows you to identify all possible hypotheses (explanations for a thing), collect available evidence that supports or refutes these hypotheses, and then identify the hypothesis that makes the most sense (is most valid).

Once you have completed the process, you will have a hypothesis that best explains the data and is most likely correct.

ACH was developed in the intelligence community and later popularized in Richards J. Heuer, Jr.’s Psychology of Intelligence Analysis (a CIA veteran and educator). In the book, Heuer describes various analytical techniques for overcoming biases when assessing intelligence. The simplest of these is the Analysis of Competing Hypotheses.

He describes how, when given intelligence (a problem) and asked to make an assessment (produce a solution), we must create several different hypotheses and choose between them to make a thoughtful decision.

To choose the most valid one, you need a framework to generate an exhaustive list of hypotheses, assess the evidence accurately, and prevent biases from creeping in. He created ACH to help solve this problem.

The book Psychology of Intelligence Analysis is free on the CIA’s Center for the Study of Intelligence website. I highly recommend reading it if you work in cyber security, particularly threat intelligence.

Since then, ACH has entered many disciplines and helped analysts, managers, and executives make key decisions by following a methodological approach that promotes critical thinking, evidence-based conclusions, and logical reasoning.

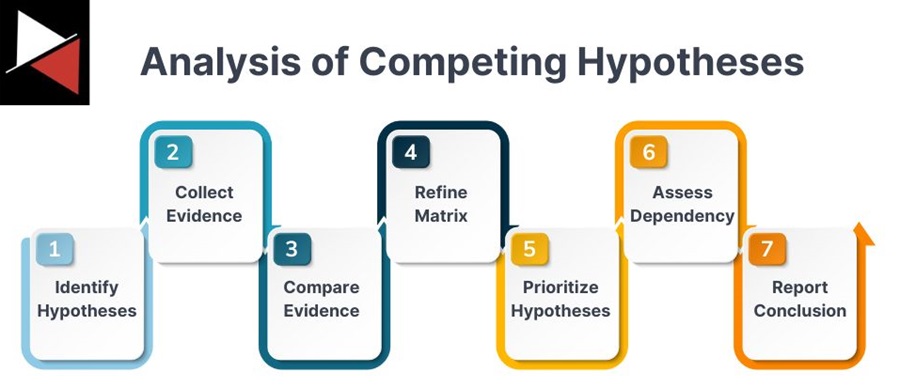

Despite its long-winded name, it is one of the more simple analytical techniques to follow with its seven-step process:

- Hypothesis: Identify hypotheses.

- Evidence: Collect evidence that supports those hypotheses.

- Comparison: Create a matrix to compare the evidence to determine the most plausible hypothesis.

- Refinement: Refine the matrix by removing invalid evidence or hypotheses

- Prioritization: Prioritize hypotheses based on their relative likelihood.

- Dependencies: Determine which hypotheses are most sensitive to evidence being wrong.

- Report: Report your most likely hypotheses to decision-makers and why you came to this conclusion. This will allow them to assess the best course of action.

Let’s examine how to go through each of these steps so you can start using ACH.

The Analysis of Competing Hypotheses Process

ACH is a structured analytical technique consisting of seven steps. These seven steps allow you to systematically evaluate and compare multiple hypotheses (explanations) for a given set of evidence or observations.

The seven steps are not designed to offer prescriptive advice that leads you to the “right” decision. Instead, they provide a structure for you to follow when assessing the validity of competing hypotheses that mitigates potential biases and promotes logical reasoning.

#1 Identifying Hypotheses

The first step is to identify as many possible hypotheses that explain a situation based on available evidence. These hypotheses should be mutually exclusive and cover all possible explanations for the given evidence, no matter how far-fetched they may seem at the time.

When developing these hypotheses, you should include others. Their diverse perspectives will allow them to generate new ideas and explanations you would have never considered. As long as the available evidence does not disprove these explanations, include them in your list of possible hypotheses.

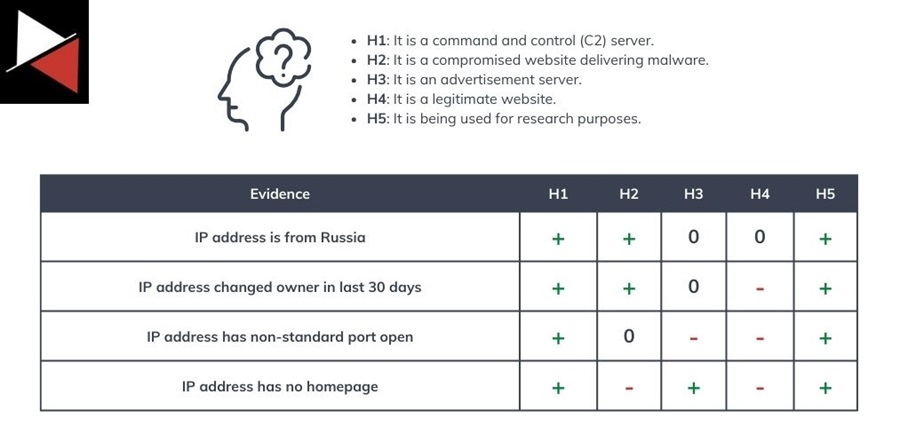

For instance, say you discover an indicator in your network logs categorized as “suspicious” by cyber threat intelligence (CTI) sources. Possible hypotheses for this IP address include:

It is a command and control (C2) server.

The IP address may be related to a C2 server an implant (agent) is beaconing to after an initial breach.

It is a compromised website delivering malware.

The IP may be a website that an attacker has compromised to deliver malware to unsuspecting victims, which is why intelligence sources are flagging it as suspicious.

It is an advertisement server.

CTI vendors often flag servers delivering advertisements as suspicious because they are unwanted and can be a potential risk if compromised. This could be the case with this IP.

It is a legitimate website.

IP addresses are ephemeral. They often change as infrastructure is created and IP addresses are recycled. A suspicious IP address from the past may now belong to a legitimate website and is being miscategorized by CTI vendors.

It is being used for research purposes.

A website may be suspicious, even malicious, but a member of your security team may be using it for research purposes. These include investigating the IP based on a CTI report or testing that security tooling can detect the Indicator of Compromise (IOC).

In the Psychology of Intelligence Analysis, Heuer emphasizes that the greater the uncertainty or impact of your conclusion, the more hypotheses you should consider. Even if there is no evidence to prove your hypothesis, you should include it as long as there is no evidence to disprove it. You may find evidence later on.

#2 Collecting Evidence

After generating hypotheses, you must gather all relevant evidence that may support or refute them. Evidence can be intelligence reports, open-source information, expert opinions, historical data, and assumptions or deductions you make about the situation.

This evidence does not need to be empirical. So long as it moves the process forward and reasonably explains the current facts, you can count it as evidence. You will refine this evidence later on in the process.

A good starting point is to assume each hypothesis is true. Review the hypotheses and note which evidence supports them and what evidence is expected but missing (and why it might be missing). This will ensure you don’t exclude hypotheses just because the evidence is currently unavailable.

#3 Comparing Evidence

Now, it’s time to compare all the evidence you collected. To do this, create a matrix of hypotheses (listed horizontally) and evidence (listed vertically). Review each piece of evidence and assess the degree to which it supports or is consistent with each of your hypotheses. You can put a plus (+) if it supports a hypothesis, a minus (-) if it does not, and a 0 if it does neither.

Some evidence will support or not support a hypothesis more strongly (e.g., it is more credible, reliable, or relevant). You can mark this with two pluses (++) or minuses (–) to indicate this.

Once you have filled out the matrix, you can move on to the next step, refining it.

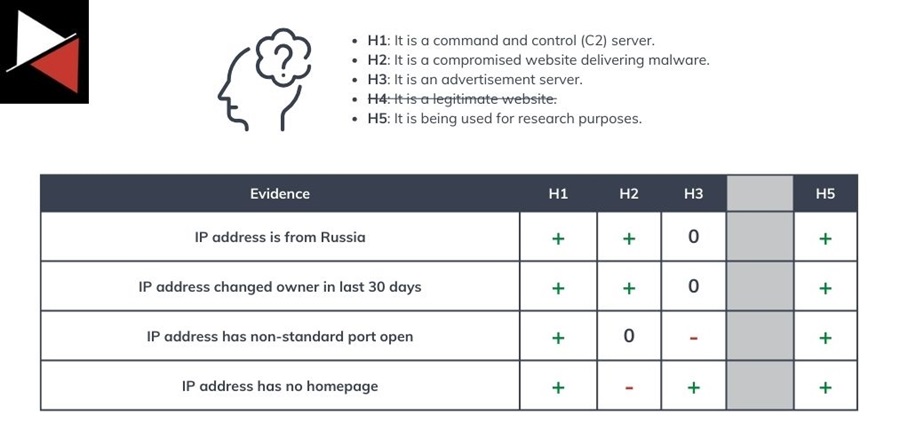

#4 Refining the Matrix

With a complete matrix, it should become apparent which evidence does not help determine the relative likelihood of your hypotheses. Remove this evidence from your matrix.

For example, the domain name a suspicious IP address resolves to is evidence. However, this may be non-diagnostic evidence that does not help determine the likelihood of a hypothesis, so it is irrelevant to your analysis.

At this step, you may also find that removing hypotheses or scrutinizing evidence uncovers new evidence or hypotheses. Add these to your matrix and compare them. Make sure to document any evidence or hypotheses added or removed so you can include them in your assessment and the reasoning for your decision.

You can move on to the next step once you have a list of possible hypotheses backed by at least one piece of evidence.

#5 Prioritizing Hypotheses

Next, you can review the relative likelihood of each hypothesis based on your collected evidence. Start by evaluating each hypothesis vertically and assess the evidence that either supports it or does not (your plus and minus symbols).

It’s good practice to start with evidence that reduces the likelihood of certain hypotheses, prioritize your list based on this evidence, and then examine supporting evidence.

This reject-first approach, which focuses on disproving evidence first, will help you manage confirmation bias. It will force you to assess the totality of your evidence rather than just evidence that supports your favorite hypotheses.

#6 Assessing Dependencies

Once you have prioritized your hypotheses from most likely to least likely, you can move on to assessing how dependent your leading hypotheses are on certain pieces of evidence.

You can ask questions like:

- Does my leading hypothesis depend on one or a few pieces of evidence?

- Do I have a high, moderate, or low confidence that a key piece of evidence is accurate?

- Could my evidence change over time, and how will this affect my hypotheses?

- Am I making assumptions about evidence that may need to be reconsidered?

You should write down your assumptions about the evidence you have gathered, note the key pieces of evidence that led you to prioritize a certain hypothesis, and describe how new evidence may affect your leading hypotheses.

Including your assumptions and evidential dependencies is crucial for decision-makers to understand the reasoning behind your conclusions and adjust their decision if new evidence emerges.

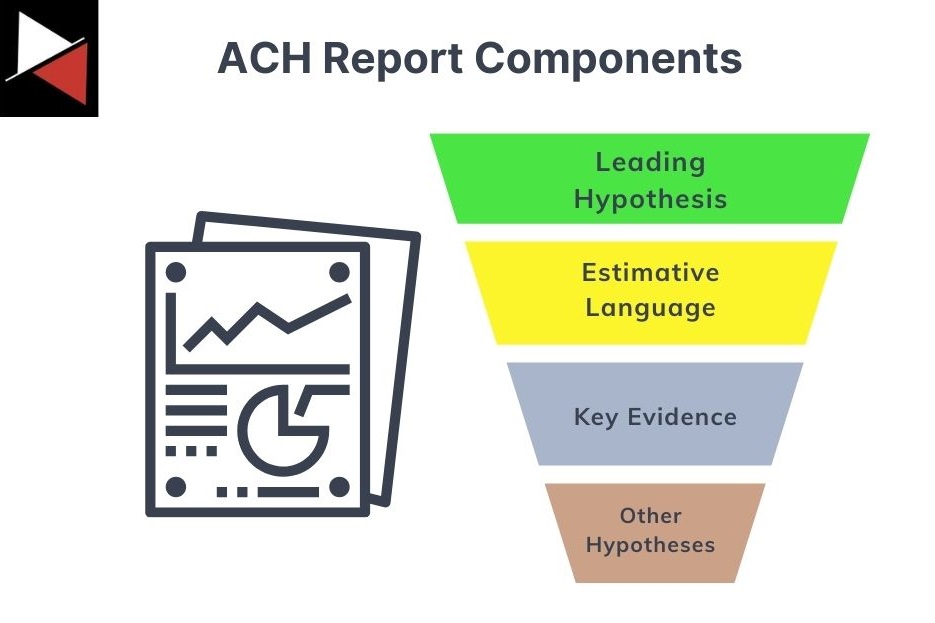

#7 Reporting Conclusions

Finally comes the report. You must write your conclusions in a coherent and succinct report explaining how you came to the hypothesis you did. This should enable a key stakeholder to make an informed decision.

Key elements to include in this report include:

- Your leading hypothesis: Always start the report with your leading hypothesis. It is what the person reading your report is most interested in.

- Estimative language: Qualify your leading hypothesis with estimative language that describes your confidence in your assessment based on the number of possibilities assessed and evidence supporting it.

- Key evidence: Support your assessment with the key pieces of evidence that led to your conclusions. Focus on the evidence instrumental in your decision and, if changed, would likely force you to reconsider your assessment.

- Hypotheses considered: Finally, briefly describe the other hypotheses you considered and your reasoning for not prioritizing them. This will help the reader understand why you reached your conclusions.

Watch the video below to learn more about these seven steps. It shows how each step flows into the next, allowing you to navigate the analytical process efficiently.

When to use the Analysis of Competing Hypotheses

Now that you know what ACH is and the seven steps that make up the process, let’s look at some common use cases.

- Intelligence analysis: ACH is predominately used to evaluate competing hypotheses regarding security threats based on collected intelligence. It helps CTI analysts evaluate each hypothesis and provide an assessment based on the most plausible one so that a key stakeholder can decide on the best course of action.

- Security research: Researchers can use ACH to structure their experiments and assess the validity of their hypotheses using empirical evidence. The technique provides a framework for testing hypotheses, analyzing data, and drawing conclusions.

- Decision-making: ACH does not need to focus only on CTI. It can be integrated into any team’s decision-making process where there are uncertainties or disagreements about root cause problems or outcomes. The technique allows you to consider multiple perspectives and base your decision on available evidence.

- Risk assessment: ACH can be used to evaluate and manage risks, such as threats, vulnerabilities, and their potential impact. This empowers vulnerability and risk management teams to prioritize risks their company faces and allocate resources effectively.

- Strategic planning: ACH is not just limited to operational teams making decisions on the ground. Managers or executives can use the technique to support their strategic planning efforts and forecast future organizational objectives and priorities using today’s evidence.

Despite ACH’s adaptability and ability to help practitioners structure their analysis, the technique also has limitations. Understanding these limitations will allow you to recognize when to use this analytical technique and when to choose another. Let’s explore them.

It is important to remember that ACH is an analytical technique developed inside the intelligence community. Therefore, it applies to many disciplines, not just cyber security. For brevity, this article only focuses on cyber use cases.

Limitations of the Analysis of Competing Hypotheses

Analysis of Competing Hypothesis is a key analytical tool you should have in your arsenal. To use it effectively, you must recognize its limitations and understand how to work around these to deliver the best analysis possible. Here are some of the analytical technique’s limitations.

- Subjectivity in evaluating evidence: ACH relies on analysts making subjective judgments about what hypotheses are credible, relevant, and significant based on the evidence they collect. There are no checks and balances. The analyst controls the entire flow of information, which can lead to missing, incomplete, or biased conclusions.

- Challenging to weigh evidence: Assessing whether one piece of evidence is more valuable, reliable, or important than another can be difficult. This can lead to uncertainty and biased conclusions. ACH tries to counter this by focusing on the number of supporting pieces of evidence, but this can lead to overreliance on quantitative metrics.

- Assumption of mutually exclusive hypotheses: ACH assumes all hypotheses are mutually exclusive, with only one being true. In reality, multiple hypotheses may be partially true and are connected by an unforeseen hypothesis. This makes analysis and interpretation challenging.

- Resource-intensive: ACH can be a resource-intensive process that requires an analyst to dedicate a large amount of time to identifying all possible hypotheses, gathering all the available evidence, and rigorously assessing the credibility of this data. This can lead to delays in the threat intelligence lifecycle.

- The analysis is fixed to a point in time: You identify all the relevant hypotheses at a certain point in time, collect available evidence, and then assess the most likely hypotheses. However, evidence changes over time, affecting your hypothesis’s validity and overall conclusion.

Many of these limitations arise from the assumption that ACH needs to be completed all at once and is unchanging. Instead, ACH can be an ongoing process that a CTI team performs whenever new evidence or a competing hypothesis emerges. As evidence changes, your team can factor it into their analysis and report its effects on previous conclusions.

You should always consider your analytical conclusions tentative and present the evidence on which they are based to decision-makers. This makes it clear how you came to the conclusions you did, leaves room for new conclusions if the evidence changes and lets you qualify your assessments with estimative language that shows you confidence in a hypothesis.

Demo: Analysis of Competing Hypotheses in Action

You have already seen some examples of the Analysis of Competing Hypotheses method in action with the suspicious IP address walkthrough earlier. To make the process more understandable, let’s look at a less technical case study that is more common to everyday life.

Case Study

Let’s focus on a common problem men (and occasionally women) face worldwide – misplaced car keys.

The situation is as follows: You step outside your house, ready to begin another day, when suddenly you realize you do not have your car keys. Being an avid cyber security analyst, you go back inside, sit at your dining room table, and use the Analysis of Competing Hypotheses technique to deduce where they are most likely to be.

Yes. In the real world, this is overkill and a waste of paper, but it is a good example of how to apply logical reasoning through ACH.

Applying Analysis of Competing Hypothesis

Let’s apply ACH to the problem of missing keys.

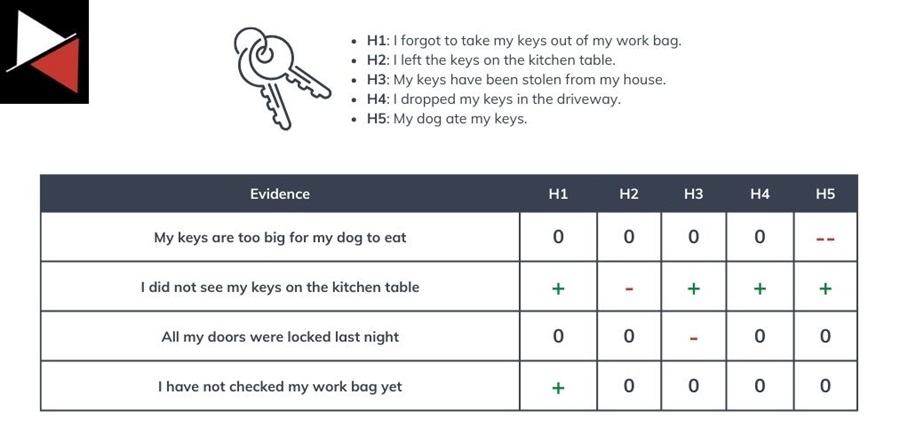

Step 1: Identify Hypotheses

We could generate several ideas about the whereabouts of the missing keys. A few include:

- I forgot to take my keys out of my work bag.

- I left the keys on the kitchen table.

- My keys have been stolen from my house.

- I dropped my keys in the driveway.

- My dog ate my keys.

You can even get Artificial Intelligence (AI) to help you generate these hypotheses. To learn more, read Learn 10 ways to use ChatGPT for Threat Hunting Right Now!

Step 2: Collect Evidence

Next, you must collect all relevant evidence that supports or refutes these hypotheses, including empirical evidence (e.g., I currently do not have the keys in my jacket) and assumptions (e.g., I amuse my keys are not in Antarctica).

Step 3: Compare Evidence

With your hypotheses generated and evidence collected, you can create a matrix listing your hypotheses horizontally and evidence vertically. You can then use this matrix to assess the degree to which a piece of evidence supports or refutes each hypothesis.

Here, a plus (+) supports a hypothesis, a minus (-) refutes it, and a 0 does neither. In addition, two pluses (++) or two minuses (–) indicate evidence strongly favoring or against a hypothesis.

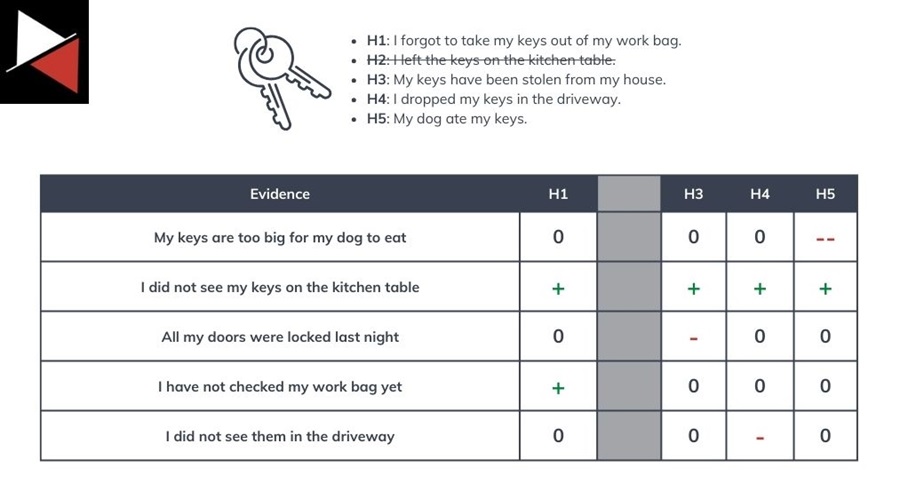

Step 4: Refine the Matrix

The next step is to review your matrix and refine it by removing or adding hypotheses or evidence. In this example, you can remove I left the keys on the kitchen table from the list and add a newly discovered piece of evidence I did not see them in the driveway.

Make sure to remove any hypothesis that does not have at least one supporting piece of evidence.

Step 5: Prioritize Hypotheses

Once your matrix is complete, you can prioritize the most likely hypotheses. As previously mentioned, it’s good to start with evidence that reduces the likelihood of certain hypotheses, prioritize your list based on this evidence, and then examine supporting evidence. This will force you to assess all the evidence you have collected and avoid confirmation bias.

The list of hypotheses, based on likelihood, in this example are:

- I forgot to take my keys out of my work bag.

- I dropped my keys in the driveway.

- My keys have been stolen from my house.

- My dog ate my keys.

Step 6: Assess Dependencies

Before you can begin telling people about your leading hypothesis, you must consider the key pieces of evidence or assumptions it depends on. If these change, they will affect your assessment or your confidence in it. Noting these is important for future analysis, as new evidence may emerge that proves assumptions false.

The key pieces of evidence in this example are:

- My keys are too big for my dog to eat

- I have not checked my work bag yet

Step 7: Reporting

Finally, you can report your findings. In this example, it is as simple as looking for your keys in your work bag. However, in the real world, you want to include your leading hypothesis, qualify it with estimative language, back it up with key evidence, and conclude with the other hypotheses you considered to support your assessment.

For more practical examples of ACH, check out this excellent YouTube video. It provides clear, simple, and easy-to-understand examples to help you understand how this structured analytical technique can be used in the real world.

Conclusion

The Analysis of Competing Hypotheses (ACH) is a structured analytical technique for identifying, comparing, and assessing the most likely explanation for a set of evidence or events. The technique’s robust process emphasizes logical reasoning and requires users to assess all the potential possibilities, allowing them to think critically and make informed decisions.

This guide taught you everything you need to know to start using ACH, from the seven-step process to real-world use cases to potential limitations and how to overcome them. It even included a practical demonstration of the technique applied to solving a problem we are all familiar with. It’s now time for you to start using the technique!

Try applying ACH to solve everyday problems like losing your keys, investigating why your kid won’t eat their food, or determining what channel the football is on tonight. This will help you get used to the ACH process and make it easier to apply it to your professional work, whether analyzing threat intelligence, sifting through intrusion data, or performing strategic planning.

You can learn more structured analytical techniques in this series.

Frequently Asked Questions

What Is the ACH Analysis Method?

The Analysis of Competing Hypotheses (ACH) is a structured analytical technique for evaluating and comparing multiple hypotheses or explanations for a given set of observations or evidence. It uses a seven-step process to identify hypotheses, gather evidence, and assess which hypothesis best explains the given evidence. ACH is predominantly used as an intelligence analysis method and is a valuable tool for any cyber threat intelligence (CTI) analyst.

Why Is It Best to Have Competing Hypotheses?

Identifying multiple competing hypotheses that explain an event allows an analyst to more rigorously assess the evidence they collect and critically consider their conclusions. An analyst must consider each hypothesis, the evidence that supports or disproves it, and the most likely explanation. This increases the robustness of the decision-making process and promotes the exploration of alternative explanations, mitigating potential biases in the analysis.

How Do You Assess a Hypothesis?

In the Analysis of Competing Hypotheses (ACH), an analyst collects evidence, evaluates its validity, reliability, and completeness, and then creates a matrix to assess whether the evidence supports a given hypothesis. Using all the evidence collected, the analyst can prioritize a hypothesis and conclude whether it best explains an event or situation.