Cyber threat intelligence (CTI) is difficult. It requires meticulous data collection, thorough investigation, and critical thinking skills. A difficulty people often forget about is CTI analysis bias and how it can entrap new analysts.

All analysts have bias. It is what makes us human. However, in CTI, you must eliminate bias to avoid inaccurate and misleading intelligence assessments that fail to accurately inform key stakeholders. This guide will show you how to avoid those biases.

You will learn what CTI analysis bias is, the different types of bias, and how to overcome bias using various strategies. This will empower you to avoid the common pitfalls many new CTI analysts fall into and produce actionable intelligence backed by evidence.

Let’s get started!

What is CTI Analysis Bias?

Cyber threat intelligence (CTI) teams follow a lifecycle to ensure intelligence requirements are met. Information is gathered, analyzed, and then distributed as intelligence to fulfill an intelligence requirement that allows key stakeholders to make informed decisions.

A key component of this lifecycle is the analysis stage. It is here that information is turned into actionable intelligence, patterns are transformed into insights, and intelligence assessments are generated. Knowledge and experience are required to understand the nature, scope, and implications of the threats present in the collected data.

Unfortunately, CTI analysis is difficult. Unlike other cyber security disciplines, like malware analysis or security operations, it requires you to go beyond technical knowledge, analysis techniques, and cyber security frameworks. You must also contend with your own innate biases.

CTI analysis biases are cognitive and systematic errors in processing, analyzing, and interpreting information. They negatively influence your judgments and lead to poor threat intelligence assessments that fail to explain the available information accurately.

Biases can be anything from a logical flaw in thinking to overreliance on single pieces of evidence. Some common ones include:

- Confirmation bias: You just look for evidence that supports your conclusion.

- Anchoring: You over-rely on the first piece of evidence you gather

- Availability bias: You over-emphasize recent or memorable events.

The difficulty in contending with biases is that we are all susceptible to them, encounter them daily, and they often go unnoticed. For example, you may have seen a tragic plane crash on the news and now feel uneasy getting on a plane, even though planes are statistically the safest form of public transport. This is availability bias.

There is more on these biases later, including what they look like when analyzing threat intelligence.

Biases persist in society because they are often useful to us as human beings. For example, it can be useful for our own survival to be biased against long, slithery things that bite you when you go near them or to stay clear of dark alleys at night (even though the chances of anything bad happening a very low). Biases can even be useful in cyber security.

When is Bias Useful?

Most cyber security professionals are paid to be biased. They need to use their knowledge and experience to come to a conclusion quickly.

For example:

- A SOC analyst must quickly perform root cause analysis to determine where a threat came from and how to handle it.

- A malware analyst must analyze malicious code to locate IOCs and TTPs as fast as possible to defend against other variants.

- A penetration tester must find as many vulnerabilities and security weaknesses as possible in a limited amount of time so a client can bolster their security posture.

Security personnel are paid to be quick, and well-formed biases allow them to do this. A SOC analyst who has seen hundreds of brute force attacks can pick up on initial indicators faster using their biases. A malware analyst can dissect malware faster by looking for specific mutexes based on their bias. A penetration tester is biased to test particular things where common vulnerabilities are found.

However, in cyber threat intelligence, you are paid to identify and overcome your biases to ensure the intelligence you produce is accurate. Let’s look at the biases you will likely encounter when performing CTI analysis.

The Different Types of CTI Analysis Bias

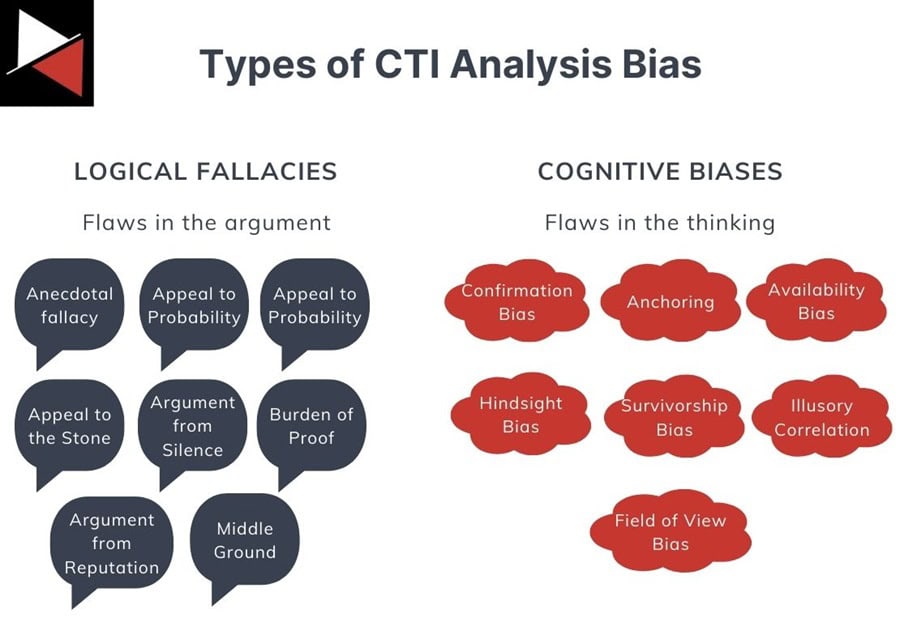

All biases stem from the need to reach a conclusion faster with less work. There are many ways to restructure your thinking to do this, but, in general, they fall into two categories:

- Logical fallacies: An error that can lead to an argument being incorrect or misleading. These can be disproven through reasoning – an error in the argument.

- Cognitive biases: A systematic pattern of thinking that leads to irrational conclusions. They are inherent in our thinking and can influence our judgments – an error in our thinking.

CTI Analysis Bias: Logical Fallacies

When analyzing intelligence or writing an intelligence report, you first want to avoid logical fallacies. These are bad arguments that involve some flaw in your reasoning. They don’t necessarily mean you are wrong; they mean that the reasoning behind your argument is flawed and does not support your conclusion.

The difficulty with logical fallacies is that they “almost” make sense and require a level of critical thinking to pull apart. Here are some common ones to be aware of.

Anecdotal Fallacy

- Fallacy: An argument based on personal experience, anecdotes, or isolated examples rather than factual evidence or logical argument. For instance, “It happened to me; therefore, it must happen to everyone, or it must be true.” Personal experiences are subjective and lead to overgeneralizations that don’t consider contradictory evidence or the broader context.

- Example: “I analyzed the intrusion and didn’t see anything suspicious, so you must be wrong.”

Appeal to Probability

- Fallacy: An argument that assumes that something will definitely happen because something is likely to occur. This fallacy overlooks the distinction between possibility and certainty, leading to flawed conclusions.

- Example: “Russia does a lot of cyber attacks against the finance industry. It must be Russia who attacked us.”

Appeal to the Stone

- Fallacy: When you dismiss an argument as absurd or untrue without providing any evidence or logical reasoning to dismiss it. You are relying on the assertion that the argument is absurd rather than justifying why it should be rejected.

- Example: “It is absurd to think a Western country would spy on its own citizens.”

Argument from Silence

- Fallacy: Accepting a conclusion due to the lack of evidence against it. This is problematic because a lack of evidence could have many interpretations (e.g., it hasn’t been found yet, there is no way to prove it with evidence, the evidence is being held back, etc.)

- Example: “I have proof it wasn’t China that attacked us, and no proof that was not North Korea, so it must’ve been North Korea.”

Argument from Repetition

- Fallacy: When an argument or claim is repeated over and over again with the hope that it will just be accepted as being valid. You’ve probably experienced this one with your partner.

- Example: “We’ve been looking at this data all day. Let’s just say Russia did it.”

Burden of Proof

- Fallacy: The person who makes an argument or claim must prove its validity. It is not up to someone to disprove your assessment. Instead, you must prove it with supporting evidence.

- Example: “Prove that it wasn’t Iran that hacked us.”

Middle Ground

- Fallacy: The erroneous belief that the truth must lie between two extremes or opposing views. You accept that a “middle ground” between two arguments must be the most valid without considering the evidence or validity of each individual argument.

- Example: “You think it is a cybercrime gang from Russia. I think it is a cybercrime gang from China. It must be a cybercrime gang.”

Want more logical fallacies? Here are 31 logical fallacies in 8 minutes. Don’t fall for them!

CTI Analysis Bias: Cognitive Biases

Avoiding making a bad argument is just the first type of CTI analysis bias you must contend with. After ensuring your conclusion does not fall prey to bad reasoning, you must stay clear of bad thinking.

Cognitive biases are flaws in interpreting information that can lead to incorrect decisions, assessments, and rationale. Each of us has our own version of reality, which is shaped by our cognitive biases. These biases help us make decisions, make sense of things, and navigate the world. However, when analyzing conceptual information and raw data, they can lead us astray, resulting in inaccurate, illogical, and irrational conclusions.

They are more difficult to spot than logical fallacies because they are ingrained in how we think and are shaped by years of experience. Combating them requires structured analytical techniques and collaboration, but more on this later.

Here are some common cognitive biases. See if you recognize any of them in your own thinking or your peers.

Confirmation Bias

- Cognitive bias: The tendency to favor information confirming our pre-existing beliefs while dismissing or ignoring evidence contradicting those beliefs. This can lead to putting greater significance on certain pieces of evidence, undervaluing valid evidence, or failing to consider other hypotheses (e.g. congruence bias – a form of confirmation bias).

- Example: “Focusing on just the fact an IP address was from Russia, even though the TTPs used during an attack align with those of Iran.”

Anchoring

- Cognitive bias: Where you rely too heavily on the first piece of information you receive, you are “anchored” on it. This prevents you from seeking new information or analyzing competing information. It often happens when you find something of value at first, so you keep pulling on that information rather than looking for other pieces of information.

- Example: “This IP address is from India so it must be an Indian threat actor I am looking for.”

Availability Bias

- Cognitive bias: Relying on readily available information when making a judgment. It causes you to overestimate the importance or likelihood of an event based on how easily you can recall the last time it happened.

- Example: “Claiming Microsoft is always breached just after they get breached for the first time in fifteen years. You can recall the event, so you assume it is common.”

Field of View Bias

- Cognitive bias: The tendency to believe that you have access to all the information when, in fact, you have a limited view. In cyber security, your view of worldwide cyber operations is very small. You do not have access to all the data and lack the ability to see attacks end-to-end.

- Example: “Claiming an attack originated in a country when you have no sources collecting data from that country.”

Survivorship Bias

- Cognitive bias: Focusing on the information that was collected or passed certain criteria while ignoring other information. This can lead to an inaccurate representation of events, incomplete evidence, or a skewed understanding.

- Example: “They must have attacked us this way because these are the only detections that we saw.”

Illusory Correlation

- Cognitive bias: Perceiving a relationship between two events or pieces of information when no such relationship exists. This is common when you discover two unusual observations.

- Example: “There is no way the data was leaked accidentally. It must have been a targeted attack from a nation-state.”

Hindsight Bias

- Cognitive bias: The tendency to perceive past events as more predictable than they actually were. For instance, an unlikely outcome is perceived as “obvious” after it has occurred. Predicting cyber threats is very difficult. Hindsight bias inappropriately simplifies that problem and diminishes the rigorous work your CTI team applies to resolve an ambiguous situation.

- Example: “Of course, it was the Russians. They always attack the US.”

You can learn more about cognitive biases in CTI by watching this excellent presentation by Raina Freeman.

Now that you know some of the biases to look out for, let’s explore how you can overcome them!

How to Overcome CTI Analysis Bias

Logical fallacies and cognitive biases are not easy to overcome. As humans, they are ingrained in us and are effective guideposts for navigating everyday life. But not all is lost. You can defeat these biases using several different strategies.

Structured Analytical Techniques

The easiest way to overcome CTI analysis bias is through structured analytical techniques. These are systematic methods for comprehensively analyzing information while remaining objective.

Examples of such techniques include:

- Analysis of Competing Hypotheses (ACH): This technique involves listing all possible hypotheses and evaluating evidence for and against each one. This helps avoid confirmation bias by forcing consideration of alternative explanations.

- Red Teaming: This security testing technique involves a separate team challenging the primary team’s assumptions and findings. This adversarial approach uncovers blind spots and counteracts groupthink.

- Devil’s Advocate: This technique involves a team member taking an opposing point of view to yours and arguing why this perspective is more valid. It helps highlight evidence you may have missed and find flaws in your original assessment.

These techniques allow you to perform consistent, comprehensive, and critical data analysis by following a structured framework or methodology. This process forces you to think critically about the information you are analyzing and requires you to support your judgments or claims with evidence.

Creating a Diverse Team

We are all susceptible to being biased. Many of us share the same biases based on our cultural and socioeconomic backgrounds and areas of expertise. If you have five people from very similar backgrounds on your CTI team, they will all likely share the same biases, which will come through on every intelligence assessment.

A great way to combat this innate bias is having diversity in your CTI team to enhance the range of perspectives and reduce potential biases.

You should create a team with different cultural, educational, and professional backgrounds so everyone can bring a different viewpoint to the analysis process. You can even include individuals from other teams and disciplines in key decisions (e.g., IT, cyber security, business operations, marketing, etc.). This will provide a more holistic perspective and negate potential biases you may have missed.

Awareness Training

Regular awareness training on logical fallacies and cognitive biases will help you (and your team) recognize and manage their biases. You can use workshops, training sessions, and scenario-based training that highlight potential biases and how to mitigate them. Case studies and real-world scenarios are great for this type of training.

Peer Review and Collaboration

The peer review process has been a staple in the scientific community for decades. Allowing your peers to review, scrutinize, and double-check your work helps identify and correct potential biases.

To incorporate this into your CTI team, you can implement a process where peers regularly review analyses to provide feedback and highlight potential biases. This can be done through written collaboration tools like Google Docs or interactive video conferencing.

I highly recommend Loom for collaboration. This technology allows you to record your screen and add audio or video commentary without video editing skills. It also allows you to work asynchronously with your team members and record documentation, standard operating procedures (SOPs), or feedback quickly and easily.

Conclusion

Cyber threat intelligence (CTI) is difficult and requires strong critical thinking skills to avoid many common pitfalls new analysts fall into. Chief among these is CTI analysis bias, where flaws in how you construct arguments (logical fallacies) and how you think (cognitive bias) can lead you astray and result in inaccurate intelligence assessments.

This guide has taught you about CTI analysis bias, common biases, and various strategies for overcoming them. You should now know how to navigate common biases and produce actionable intelligence backed by evidence.

That said, CTI analysis bias is a difficult subject to master. This is just the first in a series of articles on the topic. Next time, we will focus on one specific bias and use examples of what this may look like in the real world. This will enable you to identify and mitigate it when you encounter this bias in the real world. Stay tuned for more!

Frequently Asked Questions

What Are Biases in Intelligence Analysis?

Biases in cyber threat intelligence analysis are flaws in how an assessment makes an argument (logical fallacies) or systematic errors in how an analyst interprets information and comes to a conclusion (cognitive biases).

We all have biases. They make us human and allow us to navigate the world. However, it is vital that you identify and mitigate any biases when performing intelligence work. Otherwise, they can lead to flawed assessments, poor decision-making, and ineffective strategies.

How to Avoid Bias in Intelligence Analysis?

There are several strategies you can implement to avoid bias when performing threat intelligence analysis. These include:

- Using structured analytical techniques that force you to critically assess the information you are analyzing and support your judgments or claims with evidence. Examples include Analysis of Competing Hypotheses (ACH), red teaming, and devil’s advocate.

- Creating a diverse team with different cultural, educational, and professional backgrounds so everyone can bring a different viewpoint to the analysis process and potential biases can be identified.

- Performing awareness training to highlight common biases, what they look like, and how to mitigate them.

- Engaging in peer reviews and collaboration to review, scrutinize, and double-check intelligence work for potential biases and then correcting them.

What Are Three Common Biases?

You will encounter dozens of biases when performing cyber threat intelligence analysis. Three of the most common are:

- Confirmation bias: The tendency to favor information confirming our pre-existing beliefs while dismissing or ignoring evidence contradicting those beliefs.

- Anchoring: Where you rely too heavily on the first piece of information you receive, you are “anchored” on it. This prevents you from seeking new information or analyzing competing information.

- Availability bias: Relying on readily available information when making a judgment. It causes you to overestimate the importance or likelihood of an event based on how easily you can recall the last time it happened.